How do you measure the temperature of some of the hottest industrial environments like furnaces, boilers, and nuclear reactors where temperatures exceed 1 000°C (1 832°F) and where many types of thermometers melt and fail? With sound, of course! Let’s take a few steps back to see how this is not just possible but also more accurate than traditional thermometers.

The speed of sound is often quoted as 343 m/s or 1 234.8 km/h (767.27 mph). But this is not entirely correct. The speed of sound in dry air at 20°C (68°F) is 343 m/s. The temperature, humidity, and pressure of the air all affect the speed, but temperature has the greatest influence.

Sound travels faster in warmer air because the air molecules have more energy and so can vibrate faster, which allows the sound wave to travel faster.

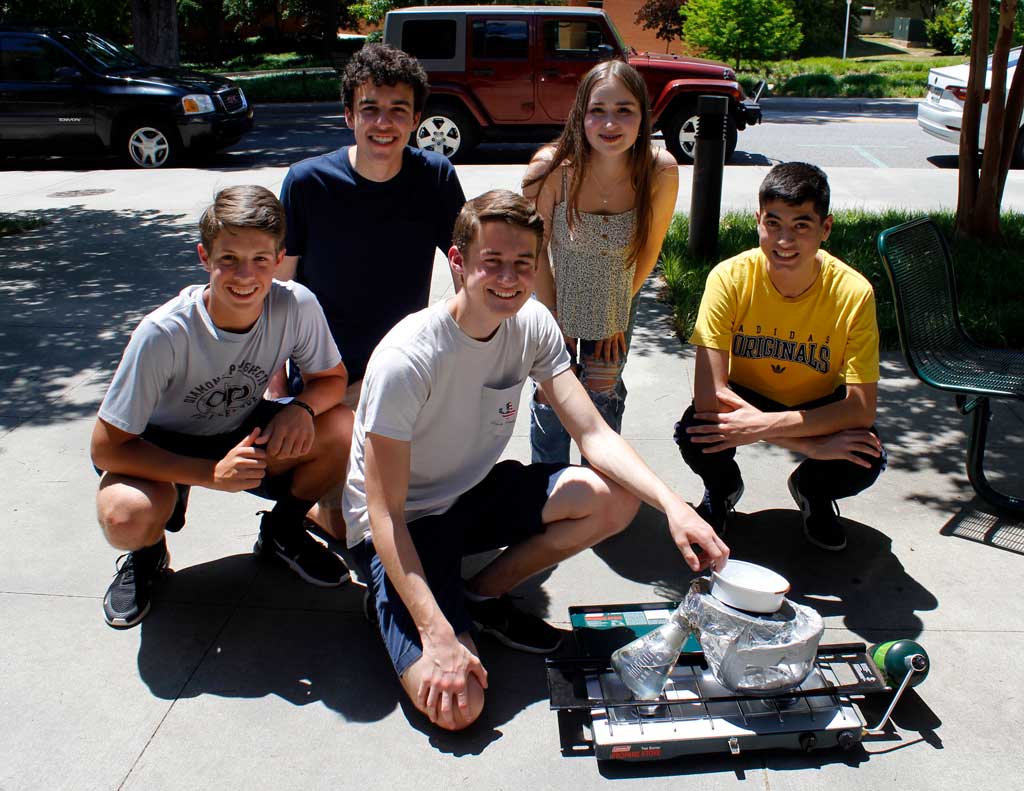

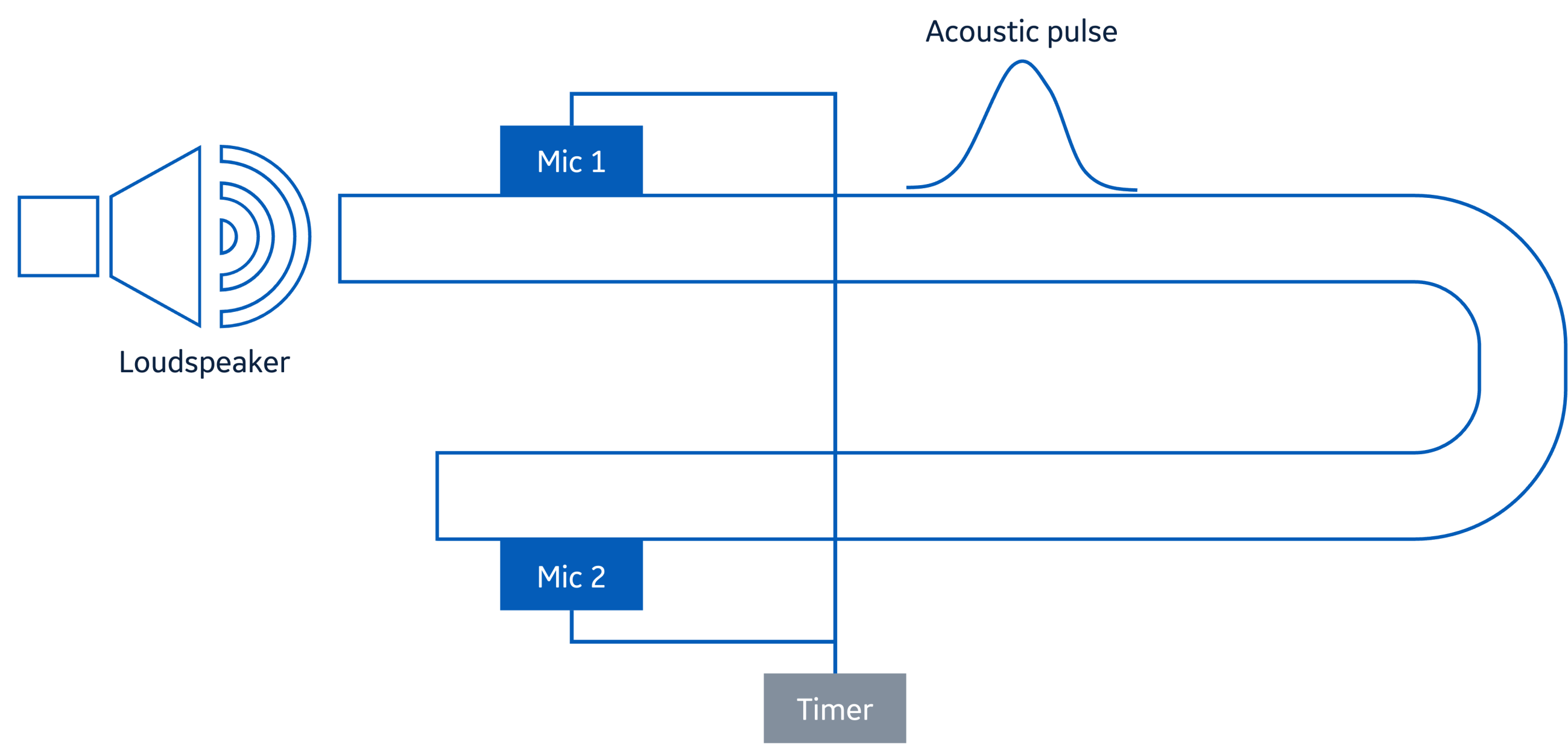

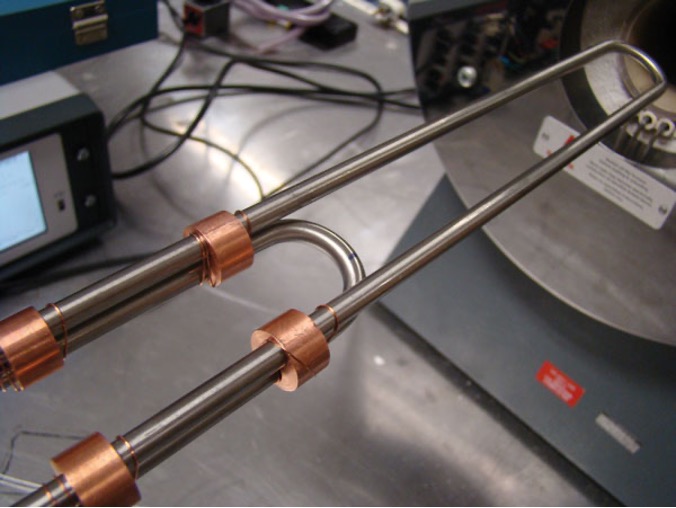

Acoustic thermometers make use of this fact. They consist of a long air-filled tube of known length at a known humidity and pressure with a speaker at one end and a microphone at the other. The tube is placed inside the hot environment and the air inside the tube heats up accordingly. A sound is then transmitted and the instrument measures how long it takes the sound to travel the length of the tube. The quicker the sound arrives, the hotter the air inside the tube is and the higher the temperature.

Acoustic thermometers like this are actually more accurate when measuring very high temperatures than more traditional or electronic thermometers. In fact, acoustic thermometers are so accurate that they are often used to calibrate other kinds of thermometers.

Michael De Podesta builds acoustic thermometers. Watch him explain how he made the world’s most precise thermometer.

Another type of acoustic thermometer measures temperatures by listening to the sounds that objects at different temperatures make. Read more about this at ScienceNews.org.

A simple formula that relates the speed of sound ($v$ in m/s) to temperature ($T$ in °C) is

$v=331 + 0.6 × T$

Use this formula to calculate the speed of sound at -20°C, 35°C, and 50°C.

Sound travels faster in water than in air. It travels at about 1 480 km/h (919 mph) in water. This is because water molecules are closer together than air molecules and so the vibration of one molecule gets transferred to the next molecule far more quickly.

Do you think sound will travel faster in water or steel?

Sometimes we forget that sound is really a form of energy - kinetic or moving energy, to be precise. This means that it can transfer energy from one location to another. Engineers have figured out how to focus high-intensity ultrasound to a very small area. This tiny area then heats up because of this focused sound energy.

This technology is used to perform certain types of surgeries, even brain surgery, without the need for cutting or opening the skull. The high-intensity ultrasound is focused onto a small part of diseased brain, often deep inside the skull. This beam heats the tissue up and destroys it.

Try measuring the speed of sound for yourself. Stand in front of a large wall (outside if possible) about 50 m (164 ft) away. Either clap or bang two flat pieces of wood together to make as loud a sound as you can. Have a friend use a stopwatch to time how long it takes the sound to return as an echo. Use this time and the total distance travelled by the sound to calculate its speed.

Watch these videos to learn more about surgery with sound.